SQL: What is Halloween protection?

If you’ve worked with SQL Server (or with databases in general) for any length of time, you will have heard someone refer to Halloween protection. It refers to a problem where update operations could inadvertently end up modifying a row more than once.

Why halloween?

The name Halloween protection comes from when the problem occurred during research on the System R project at the IBM Almaden Research Center back in 1976.

So the name comes from when it happened, rather than from anything about the problem itself. The researchers (Don Chamberlin, Pat Selinger, and Morton Astrahan) ran a query to raise everyone’s salary by 10 percent, but only if they had a salary of under $25000. They were suprised to find that after the query had completed, no-one had a salary of less than that, because the rows had been updated more than once, until they reached the $25000 value.

The name has been used to describe this problem ever since.

How do you run into this issue?

I saw someone who was pretty knowledgeable complaining about just this problem recently. He was using a dynamic cursor in SQL Server. The problem was that he was progressing along an index, but when a row was modified, it was relocated to a position in front of where he was processing, so it got processed again.

To avoid this, we need to ensure that any update operation reads the data first, and keeps a list of the values that were read, before starting to do the update. For standard updates, SQL Server does this automatically. But this guy had fallen foul of the problem by controlling things manually when using a dynamic cursor. If he had used a static cursor (which in his case would have had horrid performance), he would have been ok. Static cursors retrieve a copy of all the data before starting.

Typical updates

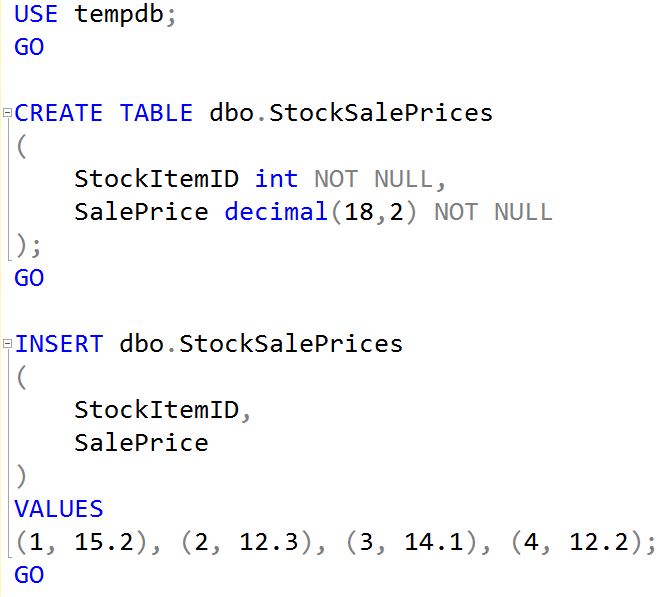

Halloween protection for standard operations isn’t about cursors though. Let’s look at how SQL Server handles this in typical updates with an example:

The query plan for that is quite straightforward:

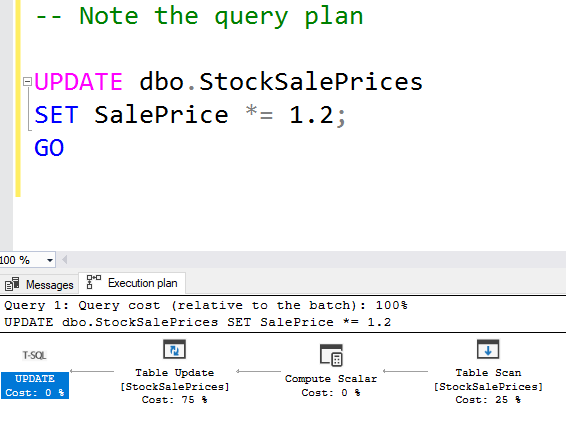

If I clustered the table on the SalePrice though, that would be a problem, and you can see how the query plan changes. Note the additional query plan step:

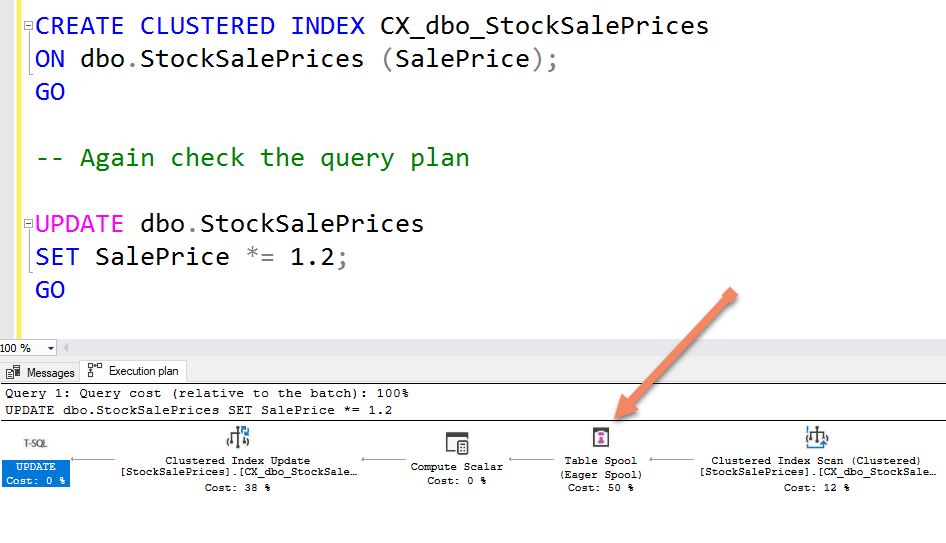

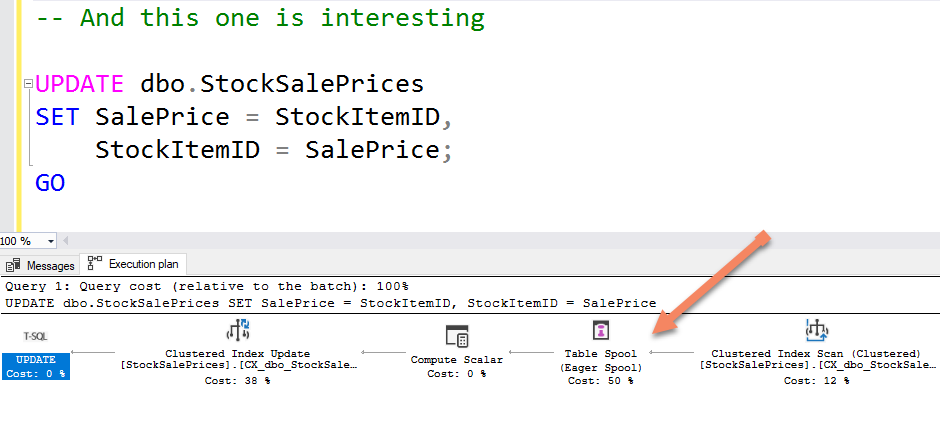

Lots of queries have this extra table spool step, and for similar reasons. It’s not for exactly the same reason but look at this query’s plan:

A = B, B = A

There are other uses for spools. One related use that surprises many people is how updates work.

In most high-level languages, you can’t just say A = B and B = A (in a single operation) to swap values over, but it works just fine in SQL. That’s because SQL Server has read the values, and has a copy of what the values were, from before the changes were made. So this is a related but different issue, but still leads to a spool operation. There are many other uses for spools.

SQL Server 2005 Optimized Halloween Protection

The core halloween issue is about avoiding rows getting updated more than once in an operation. As we’ve seen, spools have been used for that, but in SQL Server 2005, if you have Advanced Database Recovery (ADR) enabled, you can enable optimized halloween protection.

This uses a special mechanism that tracks IDs that are related to rows and are called Nest IDs. Then SQL Server ensures that a given Nest ID isn’t updated more than once in a single query.

This should make the operations faster, and reduce the load on tempdb (where the spools end up).

2025-05-30