Echoes from the field 5: Controlling stored procedure execution context (Part 1)

This is part 1 of a two-part series that shows you how to use the EXECUTE AS clause to change and control security context for stored procedures. Up next month will be digital signatures.

During a recent consulting engagement, I noticed that the client needed to control the security context that a stored procedure was running under but was using a convoluted method to do so. Changing the security context that stored procedures run under is a common requirement, letting users execute code via stored procedures that they aren’t allowed to execute directly.

There are two basic ways to control the execution context—and through it, the security context—of a stored procedure. Let’s start by exploring the use of the EXECUTE AS clause to change and control security context. Next time, we’ll look at using digital signatures for stored procedures.

Why Control Security Context?

Stored procedures are used for a variety of reasons, but two of the most important are:

- To provide a layer of abstraction, where the user doesn’t need to know how a stored procedure works internally to be able to use the procedure

- To provide a security boundary, where we can grant a user the ability to execute the stored procedure even though they do not have permission to directly perform the actions that the stored procedure performs for them.

The second reason is the one we’re interested in this time. For example, consider what happens when an operating system user executes a command to create a new folder:

C:\>MKDIR C:\TEMP\GregsFolder

Although the system administrator may be happy to let a user execute this command, he or she may not be happy to allow the same user to edit the C:\TEMP folder object directly with a binary editor. Yet, that object must be edited for the new folder to be created in it. To make this possible, we accept that the MKDIR command is able to perform actions that the user executing the command is not permitted to perform directly. Apart from basic security concerns, we want to have confidence that the C:\TEMP folder object is edited in the correct way. A user editing it directly might make editing errors.

Similar logic applies to stored procedures within SQL Server. We may grant a user permission to execute a procedure that in turn performs actions that we would not want the user to execute directly. Traditionally, this has been achieved via ownership chaining, which says that if there is an unbroken chain of ownership from the stored procedure to the underlying objects being referenced, then a user can execute the procedure without the need for permissions directly on the objects that the procedure references. Since way back in SQL Server 2005, however, other options are available.

Security Contexts

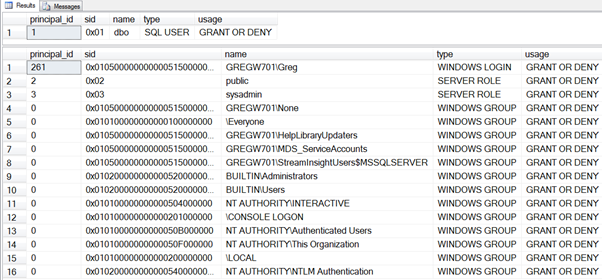

When a user is executing code in a database, a set of tokens is associated with that database user. If the database user is associated with a login, a set of tokens is also associated with the login. You can see these tokens by executing the following code:

SELECT * FROM sys.user_token;

SELECT * FROM sys.login_token;

On my system, when I first connect to the master database, these commands return the results shown in Figure 1. You can see that I have dbo rights in the database and a number of tokens related to my login.

Now let’s see how that applies to a stored procedure. First, let’s create a database to work in and a test login:

USE master;

GO

CREATE DATABASE Execution;

GO

CREATE LOGIN Test3 WITH PASSWORD = 'Test3', CHECK_POLICY = OFF;

GO

In the new Execution database, we also need to create some test users associated with these logins:

USE Execution;

GO

CREATE USER TheNobody FOR LOGIN Test3;

GO

Next, we can create a table in the database and populate it with some data:

CREATE TABLE dbo.TestTable

(

RecID int IDENTITY(1,1),

TestName varchar(35)

);

GO

INSERT dbo.TestTable VALUES('Chuck'),('Andrew'),('Frank'),

('Frederique'),('Dave');

GO

At this point, we can create a stored procedure that accesses the table and assign EXECUTE permission to the user TheNobody:

CREATE PROC dbo.GetTestTable

AS

SELECT RecID, TestName FROM dbo.TestTable;

GO

GRANT EXECUTE ON dbo.GetTestTable TO TheNobody;

GO

Now it’s time to try to execute the procedure as TheNobody. As the next listing shows, we can do this without needing to log in again by simply using the EXECUTE AS statement. The REVERT command at the end tells SQL Server to revert to our original security context. When we execute the command, the rows from the table are returned.

EXECUTE AS USER = 'TheNobody';

GO

EXECUTE dbo.GetTestTable;

GO

REVERT;

GO

Next, let’s modify the procedure slightly. In this case, we are executing the same statement via a dynamic SQL statement.

ALTER PROC dbo.GetTestTable

AS

EXEC('SELECT RecID, TestName FROM dbo.TestTable;');

GO

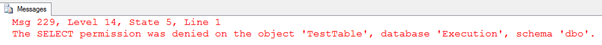

However, when we try to execute this code, we receive the error message below.

The dynamic SQL statement caused a break in the ownership chain. Previously, I owned the table as well as the stored procedure, so I could grant a user permission to execute the stored procedure, and they could access the table.

A dynamic SQL statement, however, doesn’t recognize ownership chaining. To help, SQL Server provides the WITH EXECUTE AS clause (which is different from the EXECUTE AS statement). To see the WITH EXECUTE AS clause in action, we need to alter the stored procedure again.

ALTER PROC dbo.GetTestTable

WITH EXECUTE AS OWNER

AS

EXEC('SELECT RecID, TestName FROM dbo.TestTable;');

GO

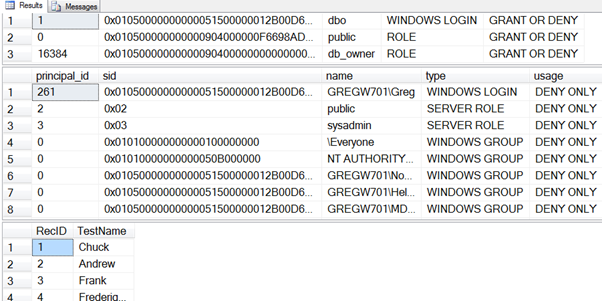

When we re-execute the procedure as TheNobody, the code works, and the user is able to see the table data. We can use the user and login tokens mentioned earlier to find out why. Let’s alter the procedure again, selecting from the sys.user_token and sys.login_token tables, as Listing 8 shows.

ALTER PROC dbo.GetTestTable

WITH EXECUTE AS OWNER

AS

SELECT * FROM sys.user_token;

SELECT * FROM sys.login_token;

EXEC('SELECT RecID, TestName FROM dbo.TestTable;');

GO

Now when we execute the procedure as TheNobody, we see the output below:

Note that even though the code is being executed as TheNobody, within the stored procedure, the code is executed in the db_owner role.

The WITH EXECUTE AS clause has four options:

- WITH EXECUTE AS CALLER – This is the default action, with the code executing as the caller.

- WITH EXECUTE AS SELF – In this case, the code executes as the person creating the stored procedure.

- WITH EXECUTE AS OWNER – The code executes as the owner of the stored procedure.

- WITH EXECUTE AS USER – The code executes as a specific identity.

The creating code that executes as another user requires the IMPERSONATE permission on that user. sysadmin logins already have IMPERSONATE permission on all users.

As we’ve seen this time, the WITH EXECUTE AS clause provides one effective way to control the execution context of a stored procedure. A second option is to digitally sign the stored procedure with a certificate. I’ll show you how that’s done in the next article in this series.

2025-11-06