Echoes from the field 4: Unique indexes vs unique constraints

Uniqueness can be implemented by primary keys, unique constraints and unique indexes. The use of primary keys is well understood but confusion exists about unique constraints and unique indexes.

This issue arose from a consulting engagement I was performing earlier in the month. During one of the architectural discussions I was having with the client, an interesting question was suddenly posed: When would you ever use a unique index?

After thinking about this for a moment, I suddenly realized that I almost never would use one and so I raised the topic on a technical discussion forum. An interesting discussion ensued and I’ve summarized the key thoughts in this article.

Enforcing Uniqueness

There are three basic ways that you can constrain a column (or group of columns) to be unique: primary keys, unique constraints and unique indexes. The use of primary keys seems to be well understood, even if the discussion of natural vs surrogate keys is endlessly debated with near religious fervour but quite a bit of confusion seems to exist around the use of unique indexes vs unique constraints.

In database terminology, a candidate key is a key that is capable of uniquely identifying a row. The key cannot be NULL and can be constructed from one or more columns. One of the candidate keys can be nominated as the primary key for the table, as shown in the following code:

CREATE TABLE Reference.Countries

(

CountryID nvarchar(3) NOT NULL -- ISO 3 country code

CONSTRAINT PK_Reference_Countries PRIMARY KEY,

CountryName nvarchar(255) NOT NULL

);

Note that I have a strong preference for naming constraints rather than leaving the naming choice to SQL Server as it tends to pick obscure names. If the key needs to be nullable, we can define a UNIQUE constraint instead.

In SQL Server, only one row can then be NULL. That is at odds with many other database engines where a UNIQUE constraint only indicates that a key is unique if it is present. The UNIQUE constraint can be placed within the definition of a column as in the following code:

CREATE TABLE Reference.Countries

(

CountryID nvarchar(3) NOT NULL -- ISO 3 country code

CONSTRAINT PK_Reference_Countries PRIMARY KEY,

CountryName nvarchar(255) NOT NULL

CONSTRAINT UQ_Reference_Countries_CountryName UNIQUE

);

The UNIQUE constraint can also be placed on an entire key or set of columns, by defining it at the table level, as in the following code:

CREATE TABLE Reference.Regions

(

RegionID INT IDENTITY(1,1)

CONSTRAINT PK_Reference_Regions PRIMARY KEY,

StateCode nvarchar(2) NOT NULL,

RegionCode nvarchar(10) NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT UQ_Reference_Regions_StateCode_RegionCode

UNIQUE (StateCode, RegionCode)

);

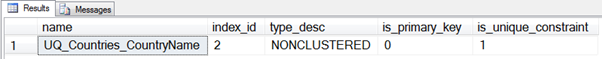

When we define a unique constraint, SQL Server will internally create an index to support this constraint. We can see the index that is created by executing the following code:

SELECT name, index_id, type_desc,

is_primary_key, is_unique_constraint

FROM sys.indexes

WHERE name = N'UQ_Reference_Countries_CountryName';

It returns the following output:

Note that SQL Server automatically created an index. It is a non-clustered index; it is flagged as a unique constraint and the internal index that has been created has been given the same name as we assigned to the UNIQUE constraint.

We can also force the values in a key to be unique by defining a unique index on the key. This is very similar to defining a UNIQUE constraint on a table but is not identical. In the Reference.Regions example above, we could have declared the table and the unique index like this:

CREATE TABLE Reference.Regions

(

RegionID INT IDENTITY(1,1)

CONSTRAINT PK_Reference_Regions PRIMARY KEY,

StateCode nvarchar(2) NOT NULL,

RegionCode nvarchar(10) NOT NULL

);

GO

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX UQ_Reference_Regions_StateCode_RegionCode

ON Reference.Regions (StateCode, RegionCode);

GO

If you again queried the sys.indexes view, you will notice that what is created is very similar but does not have the is_unique_constraint flag set to 1.

Uniqueness and Performance

Earlier I’ve described uniqueness as a business requirement, not a performance-related issue, so we should spend a moment considering if there are performance-related impacts of uniqueness.

I find that one of the most common database schema design errors is to ignore placing UNIQUE constraints where they should be used. For example, consider the table of countries defined above. Common sense tells us that the CountryName would also be unique yet it is very common to see designs where a primary key is assigned to the table but no UNIQUE constraint is added to columns such as CountryName.

There are two downsides to this error. The first is a business issue in that we could create two countries with the same name but the other issue is a performance one.

Imagine a table holding individual sales for each country. It might be defined like the following code:

CREATE TABLE Sales.SalesDetails

(

SalesDetailID int IDENTITY(1,1)

CONSTRAINT PK_Sales_SalesDetails PRIMARY KEY,

Amount decimal(18,2) NOT NULL,

SalesDate datetime NOT NULL,

CountryID nvarchar(3) NOT NULL

CONSTRAINT FK_Sales_SalesDetails_Countries

REFERENCES Reference.Countries (CountryID)

);

Note that I’ve only included a few relevant columns for simplicity. Now imagine a query that summarizes sales by country such as the following:

SELECT c.CountryName, SUM(sd.Amount) AS TotalAmount

FROM Reference.Countries AS c

INNER JOIN Sales.SalesDetails AS sd

ON c.CountryID = sd.CountryID

GROUP BY c.CountryName

ORDER BY c.CountryName;

If we were writing a query by hand, it might occur to us to group the Sales.SalesDetails rows by CountryID and then to use the summarized rows to join to the Reference.Countries table. However, most end users that are using a query tool will choose to sort their results by CountryName, not by CountryID. They probably won’t even return the CountryID so they would not think to group by it instead of CountryName.

If we have a UNIQUE constraint on the Reference.Countries table, then SQL Server knows that grouping the sales rows by CountryID is equivalent to grouping the joined table by CountryName. The problem is that without the UNIQUE constraint, SQL Server then has to join every row of the Sales.SalesDetails table to the Reference.Countries table and then sort the entire result set by the CountryName.

This is a very expensive sorting operation.

This means that adding the UNIQUE constraint then has a major impact on the performance of this query, not just on the business implications of avoiding duplicated country names. The same performance benefit would have been gained by adding a unique index on the CountryName column. What is of further interest in this situation is that the DMV sys.dm_db_index_usage_stats will not show that index ever being used, even though its presence has materially affected the execution plan that was generated.

Constraints vs Indexes

Given this unique requirement could have been implemented via either a constraint or an index, which is preferable?

In general, I would prefer to have this declared as a constraint, every time. Indexes are mostly used externally to enhance performance or internally (by SQL Server) to implement constraints. Uniqueness is normally a business-related requirement that you do not wish to have any chance of being separated from the definition of the table.

There are a few situations though that might lead you to consider a unique index rather than (or in addition to) a constraint.

First, since SQL Server 2008, we have the ability to create filtered indexes. This could help us get around the limitation where SQL Server only allows us to have a single NULL key in a UNIQUE constraint.

Second, we might want to add columns to the index to avoid lookups and to help create covering indexes. We do this via the INCLUDE clause of the CREATE INDEX statement. We currently have no way of specifying that we want columns included in the internal index that SQL Server creates to support UNIQUE constraints.

Third, when we create a UNIQUE constraint, we have no way to specify that the index created to support it should be ascending or descending. In a few (albeit rare) situations, this might concern us.

2025-11-02