Echoes from the field 3: Views, stored procedures, and abstraction

You shouldn’t have to know how a view or stored procedure works or its internal code structure to use it. To that end, it’s time that stored procedures expose detailed contracts.

Many DBAs don’t allow users direct access to tables in SQL Server databases and instead give them access only via a series of views and stored procedures. One of the cited benefits of this approach—beyond providing a security boundary—is that the views and stored procedures provide a layer of abstraction over the underlying data.

In other words, users don’t have to know how a stored procedure works to be able to use it. However, views and (in particular) stored procedures provide, at best, a leaky abstraction. Let’s look at how views and stored procedures currently provide abstraction and some changes that would improve those capabilities.

So What’s the Problem?

I shouldn’t have to know how an object works or how its internal code is structured to be able to use it. I should be able to find out all I need to know via the metadata associated with the object. Let’s see how well views and stored procedures deliver on this goal.

Views

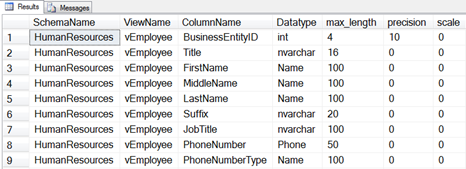

Views don’t do too badly in providing sufficient metadata about themselves. By combining details from a few system views, we can find out a lot of information about the view. For example, executing the following query against the AdventureWorks database returns the output shown below:

SELECT s.name AS SchemaName,

v.name AS ViewName, c.name AS ColumnName,

t.name AS Datatype, c.max_length, c.precision,

c.scale

FROM sys.views AS v

INNER JOIN sys.schemas AS s

ON v.schema_id = s.schema_id

INNER JOIN sys.columns AS c

ON v.object_id = c.object_id

INNER JOIN sys.types AS t

ON c.user_type_id = t.user_type_id

ORDER BY s.name, v.name, c.column_id;

In fact, by combining information from a number of views, we can find out almost everything we need to know about using the view, except for one key aspect: What is the view intended to provide? There is no description of the view.

Hopefully, the name of the view makes this fairly clear (and I admit that I’m not a fan of prefixes such as the v prefix above), but we really need more than the name to understand the purpose of a view.

If you script out the above view, you’ll see an additional line of code. Microsoft has used the ability to add an extended property to an object to provide a more meaningful description. The extended properties for an object are discoverable via the sys.extended_properties system view. The problem with this is that there is no standard for naming these properties. However, within your own organization, you could make a rule that you always have a Description extended property for each view.

EXEC sys.sp_addextendedproperty @name=N'MS_Description',

@value=N'Displays the contact name and content from each element in the

xml column AdditionalContactInfo for that person.' ,

@level0type=N'SCHEMA',@level0name=N'Person',

@level1type=N'VIEW',@level1name=N'vAdditionalContactInfo';

Stored Procedures

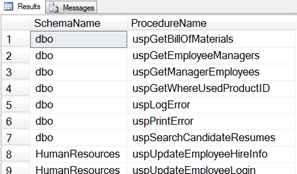

We can gain a different set of information for stored procedures. The query below is useful for returning a list of the procedures in a database:

SELECT s.name AS SchemaName,

p.name AS ProcedureName

FROM sys.procedures AS p

INNER JOIN sys.schemas AS s

ON p.schema_id = s.schema_id

ORDER BY s.name, p.name;

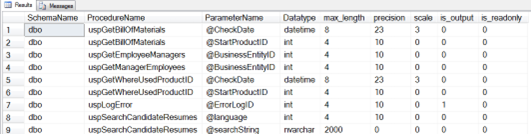

We can also find details about the parameters associated with the procedures by executing the following query:

SELECT s.name AS SchemaName, pro.name AS ProcedureName,

par.name AS ParameterName, t.name AS Datatype,

par.max_length, par.precision, par.scale,

par.is_output, par.is_readonly

FROM sys.procedures AS pro

INNER JOIN sys.schemas AS s

ON pro.schema_id = s.schema_id

INNER JOIN sys.parameters AS par

ON pro.object_id = par.object_id

INNER JOIN sys.types AS t

ON par.user_type_id = t.user_type_id

ORDER BY s.name, pro.name, par.name;

However, the big question is, How do I know what rows will be returned from a stored procedure? And the answer is that, really, you can’t. The rows returned are totally dependent on the logic of the procedure.

SET FMTONLY ON

One option for finding what rows a stored procedure returns is to use SET FMTONLY ON. Once this option is enabled on a connection, you can execute a stored procedure and get details of the metadata for the rows but no data. This technique is used by tools such as SQLMetal (which is part of LINQ to SQL) to retrieve details about stored procedures.

Although this method might seem useful at first glance, the problem is that it still has no idea which parts of the procedure logic will or will not be executed. It simply returns metadata for all rowsets that could be returned by any logical path through the stored procedure. So for very simple CRUD (create, read, update, delete) stored procedures, this option works fine. But as soon as any complexity is added to the procedure, this approach falls down.

Dependency views

SQL Server 2012 introduced a series of dependency views. These do a better job of finding objects that procedures depend upon, and objects that depend upon the procedure. But it’s still a long way from what’s needed.

What’s Really Needed?

If you want to be able to use a stored procedure without knowledge of how it works internally, you need details about many things:

- Attributes of the procedure itself. We need the obvious information such as schema, name, description, etc. We can get most of these details from the query in Listing 3 and by adding an extended property for a description.

- Details about the input and output parameters. We need parameter names, data types, lengths, precisions, scales, input vs. output, readonly information, and so on. We can also get most of this information from the queries shown earlier.

- Details about the procedure’s return value. The return value of a procedure is interesting. It has no name, but ideally, it would have a name or at least a description. Many people use it to return an integer, with zero indicating success and other values indicating an error. Other DBAs use it to return business items, such as counts of rows affected or the inserted order number. Ideally, you’d use an OUTPUT parameter for that. Regardless of how you use the return value, you need to have information about what the value represents.

- Details about all possible rowsets that could be returned from the procedure, including columns, data types, and so on, as well as details about what the rowsets represent (e.g., sales order headers). As mentioned, we currently don’t have good information on the rowsets that might be returned. SQL Server 2012 added a procedure that can describe the first rowset that might be returned, but this again is very limited, and only works for a single rowset.

- Exceptions that could be thrown within the procedure. It would be really valuable to have details about errors that can be raised by the procedure. Although unhandled exceptions are always possible, if we knew that we might raise an error 55010 indicating no such customer, for example, there should be a way to find this information without having to read the entire procedure’s code.

I see the combination of all the above needs as defining a contract for a stored procedure. Contracts are important when different teams are building different parts of an application that need to interoperate. I’d love to see syntax such as that below, to define a contract for a stored procedure.

What I’m really proposing in this column is the ability to give a stored procedure contract a name and to define within the contract details about rowsets that could be returned, the meaning of any return value, and the list of known exceptions.

CREATE OR ALTER PROCEDURE SomeSchema.SomeSproc (someparameters)

WITH CONTRACT SalesOrderHeaderAndDetails ENFORCED

(ROWS OrderHeaders(SomeColumn INT,

SomeOtherColumn NVARCHAR(50) NULL),

OrderDetails(AnotherColumn INT,

YetAnotherColumn INT,

EvenYetAnotherColumn GEOGRAPHY),

RETURNS OrderCount(INT),

EXCEPTIONS NoSuchCustomer(50020,'No such Customer'),

DuplicateOrder(50022,'That order already exists')),

Do you think that would be helpful? Even if it wasn’t directly used by a developer, development tools could use this information. In the end, you shouldn’t need permission to read the code of a procedure, to be able to use it effectively.

2025-10-29