SQL: Design – Entity Attribute Value Tables (Part 2) – Pros and Cons

In an earlier post, I discussed the design of EAV (Entity Attribute Value) tables, and looked at why they get used. I’d like to spend a few moments now looking at the pros and cons of these designs.

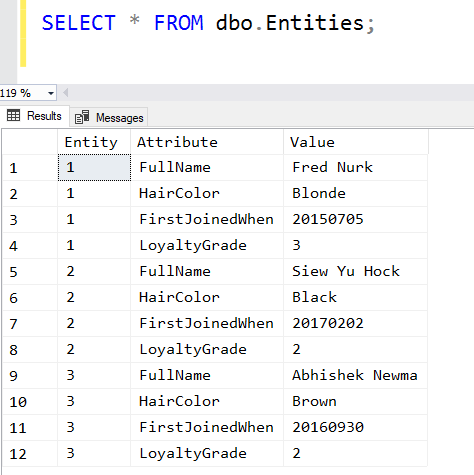

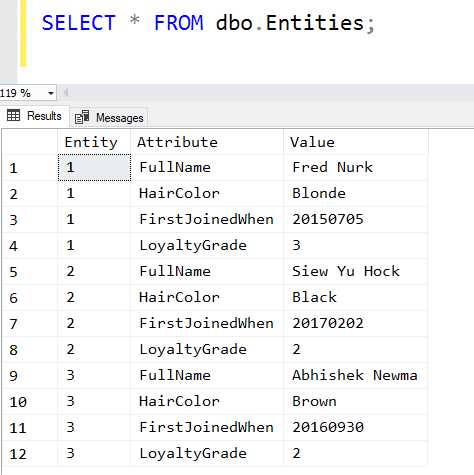

Let’s use the same table as the last time as an example:

Pros

The main positive that’s typically described is that the schema is “flexible”. By this, the developers usually mean “I don’t have to change the database schema (or worse, have someone else change it) when my needs change”.

I don’t buy this argument. Databases do a great job of managing metadata. Why would your app do it any better? I’ll be there’s another reason (perhaps political) as to why this argument is being put forward in most cases.

Another argument is that this type of design handles sparse data gracefully. When we designed the WideWorldImporters database for Microsoft, we had a few edible products. The vast majority of the products were not edible. So the question is about where a use-by-date for an edible item should be stored. Should every product have that column?

Sparse columns in SQL Server deal with that quite well, but in SQL Server 2016, we also wanted to showcase some of the new JSON-based functionality, so we ended up putting this info into a JSON-based column. I would have been just as happy with a sparse column for this though. AT least that would have allowed us good control over the data type.

Cons

I see many problems with these tables.

The most obvious problem is that a large number of joins is required to get all the related data for an entity if you ever need to process this within the database. Many of these applications, though, just read and write the entire entity each time and aren’t concerned about this. These applications though tend to be at the small end of the market and aren’t too concerned about performance.

A second key issue is data typing. In the example above, what data type is the Value column? It’s most likely some sort of string. If you’re one of the cool kids, it might be a sql_variant instead. In this case, let’s assume it’s a string of some type. How can we then provide any sort of guarantees on what’s stored in the column? The LoyaltyGrade is clearly an integer in this example, but there’s nothing to stop us putting Gold in that field instead.

Ah, but “the app does that” I’m told. That might be true but apps have bugs, as do ETL processes that put data in those fields. That’s also very small-system thinking as most organizations will have a large number of applications that want to access this same data, and they won’t even be built on the same technology stack, so lots of luck forcing all the access through your app or services layer. Ever tried to connect something like Excel to a service?

What I often then eventually see is typed columns within the table:

- StringValue

- IntValue

- DateValue

- DecimalValue

and so on. Then we have to consider what it means if a value happens to be in more than one of these. (Ah yes, the app won’t allow that).

Once again though, what you’re doing is building a database within the database, just to avoid adding or dropping columns.

Yet another problem is the complete lack of referential integrity. You have no way (or at least no ugly way) to ensure that values lie in a particular domain. Is it OK for Brunette to be entered rather than Brown for the hair color? If not, how do you enforce that? (I know, I know, the app does that).

These are just a few of the issues, and there are many more.

Before I finish for today, I do want to mention yet another design that I saw recently. Instead of one table to rule them all, with an EAV-based-non-design, what this database contained was a table for each data type. Yes there was a string table, an int table, a date table, etc.

It should be obvious that such a design is even nastier.

2018-02-19