SQL: Columns - how big is too big?

When designing databases, one question that comes up all the time is how large columns should be.

For numbers, the answer is always “big enough but not too big”. This week I’ve been working at a site where the client numbers were stored in int columns. Given the clients are Australians and the Australian Bureau of Statistics Population Clock says there are just under 25 million of us, an integer seems a pretty safe bet, given it can store positive numbers up over two billion. It’s hard to imagine that number being exceeded, but I’ve seen people deciding that it needs to be a bigint. I doubt that. Even if we count all our furry friends, we aren’t going to get to that requirement.

I was recently at a site where they were changing all their bigint columns to uniqueidentifier columns (ie: GUID columns) because they were worried about running out of bigint values. In a word, that’s ridiculous. While it’s easy to say “64 bit integer”, I can assure you that understanding the size of one is out of our abilities. In 1992, I saw an article that said if you cleared the register of a 64 bit computer and put it in a loop just incrementing it (adding one), on the fastest machine available that day, you’d hit the top value in 350 years. Now machines are much faster now than back then, but that’s a crazy big number.

For dates, again you need to consider some time into the future. It’s likely that smalldatetime just isn’t going to cut it. Most retirement fund and insurance companies are already working with dates past the end of its range. What you do need to consider is the precision of the time if you’re storing time values as well.

The real challenge comes with strings. I’ve seen developer groups that just say “make them all varchar(max)” (or nvarchar(max) if they are after multi-byte strings). Let’s just say that’s not a great idea.

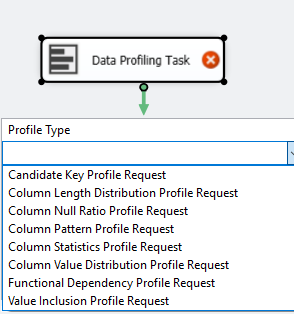

But if they aren’t all going to be max data types, what size should they be? One approach is to investigate the existing data. If you haven’t used it, SQL Server Integration Services has a Data Profiling Task that’s actually pretty nice at showing you what the data looks like. If you haven’t tried it, it’s worth a look. It can show you lots of characteristics of your data.

One thing that I see people miss all the time though, are standard data items. I was at a site yesterday where sometimes email addresses were 70 characters, sometimes 100 characters, other times 1000 characters, and all in the same database. This is a mess and means that when data is copied from one place in the database to another, there might be a truncation issue or failure.

Clearly you could make all the email addresses 1000 characters but is that sensible? Prior to SQL Server 2016, that made them too big to be in an index. I’m guessing you might want to index the email addresses.

So what is the correct size for an email address? The correct answer is to use standards when they exist.

To quote RFC3696:

In addition to restrictions on syntax, there is a length limit on email addresses. That limit is a maximum of 64 characters (octets) in the “local part” (before the “@”) and a maximum of 255 characters (octets) in the domain part (after the “@”) for a total length of 320 characters.

So my #1 recommendation is that if there is a standard, use it.

2017-11-27